Can the GOP put together a Jacksonian coalition? Lessons of History: Bank Bailouts, Kentucky

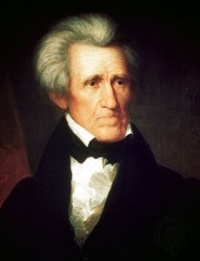

and Andrew Jackson

Kentucky is about to enter into a decade of celebrating unique historical events that shaped and built the foundation of the 14th state as it entered into the newly created United States of America. In 1792, Kentucky became the first state to be created west of the Appalachian Mountains. In 1796, Tennessee, followed by becoming the 15th state to enter the union. By 1800, tremendous pressure was building all along the new American frontier for land to be sold to new settlers in the Ohio, Tennessee, and Mississippi River Valleys.

Dreams of empire, land speculation, new cities, global trading partners, were a daily constant political force emerging in Kentucky and Tennessee. After the Louisiana Purchase of 1803, these two states became the center of the new expanded United States.

Important dates during this time of conquering the frontier were: 1811 and 1812, Great Earthquake along Mississippi River and West Kentucky; War of 1812 and Kentucky militia’s role in that conflict; 1814 and Battle of New Orleans with Kentucky long riflemen; 1818 Andrew Jackson purchasing all of West Kentucky and Tennessee from native Americans; 1819 Land speculation and bank collapse; and 1820 as the closing of Americas First Frontier.

Money and cheap credit was badly needed in this new frontier to make it worth while for the Scot Irish settlers to battle Native Americans over who would own the land of the wilderness.

Enter the bankers, legislators, and politicians.

One figure and lone leader of this geography and time was Andrew Jackson, a complex man with fierce loyal supporters and equally fierce opposition to every thing he stood for. This sprit of Jackson against big banks is now once again being discussed on a national stage. Leading voices from the GOP and conservative publications are re examining how Andrew Jackson dealt with out of control money interest, big government and failed banks.

The following paragraphs are used with permission from “Breaking the Bank: Can the GOP follow Andrew Jackson back to power?” by Sean Scallon in the September 2009 edition of the New Conservative magazine.

...”The secrecy and concentrated financial power of central banking has always aroused populist suspicions. The chartering of the first Bank of the United States (BUS) in 1791 quickly gave rise to opposition, which saw Alexander Hamilton’s brainchild as undemocratic, monopolistic, a tool of foreign stockholders, and a betrayal of the Revolution, since colonists had rebelled as much against the economic policies of the Bank of England as against the Crown itself. Once Thomas Jefferson’s popular Republican Party rose to power, the bank’s doom was assured. President Madison allowed its charter to lapse in 1811.

But after the War of 1812, Madison changed his mind. He supported chartering a second Bank of the United States to stabilize the war-wracked nation’s finances and curb the influence of local paper-issuing banks. Demand for credit in the young Republic soared after Kentucky became a state in 1792 and Tennessee joined the Union in 1796, as settlers poured into these states and pressed further south and southwest. These frontiersmen were Andrew Jackson’s people—Scots-Irish from Pennsylvania, Virginia, and the Carolinas. Between 1817 and 1818, the Kentucky state legislature, in what social historian William Graham Sumner called “bank mania,” chartered 40 small banks to lend settlers money. The Bank of the United States, far from quelling this credit expansion, got in on the act by opening branches in Louisville and Lexington. The result was a classic speculative bubble that finally burst in the Panic of 1819, sending the Mississippi and Ohio valley regions into a collapse that took five years to liquidate.

Local banks, including Kentucky’s state-run Bank of the Commonwealth, deserved most of the blame. But the BUS (Bank of the United States) had done its part to feed the speculative frenzy, and further resentment of the bank was stoked by the Supreme Court’s McCullough v. Maryland decision, which ruled that states could not tax the BUS but the BUS could tax local banks to the tune of $60,000 each. The Bank of the United States received over $600,000 from former shareholders in Commonwealth Bank, while many settlers lost their land. Weren’t these frontiersmen, whose Kentucky Rifles had won the Battle of New Orleans, only doing what the federal government wanted by populating this area from the eastern mountains to the Mississippi River and beyond?

Jackson had hated what he called “rag, tag banks” since he was a young shopkeeper and land speculator in Tennessee. Favoring hard currency, he believed banks issued “wretched rag money” and the credit they lent only encouraged indebtedness. But Jackson had no particular problem with the Bank of the United States until one was thrust on him in 1832. He was drawn into the bank wars by advisers from Kentucky and Tennessee, who bore grudges for what had happened in 1819, and by bank supporters like Sen. Henry Clay, who thought that making early renewal of the bank’s charter an issue in the upcoming presidential election would split Jackson’s Democrats and secure for Clay’s National Republicans the electoral votes of Pennsylvania, where the bank was based and remained very popular. The bank was also an important part of Clay’s financial program, his “American System” of government-sponsored domestic projects such as roads and canals.

BUS President Nicholas Biddle was a young reformer when he took the job in 1823 and did his utmost to keep politics out of the bank’s deliberations. But it was an impossible task, especially on the local level where politicians either clashed with branch officials or became recipients of their patronage. Every time Biddle tried to assert the bank’s independence, in often arrogant and sulfurous language, he played into his enemies’ hands. In trying to keep politics away from the BUS, he argued that it should be an elite institution in an age that celebrated popular democracy.

Biddle no more wanted to make the bank an issue than Jackson did. But Clay insisted, and thus the BUS applied for a charter renewal in 1832. Congress approved it, but Jackson applied the veto. The BUS resorted to politics in an attempt to save itself, but Biddle’s hardball tactics only confirmed the image the Democrats projected of the BUS as an aristocratic moneyed institution looking to crush Jackson, the common man’s avatar. The BUS spent over $100,000 to defeat Jackson. It subsidized anti-Jackson newspapers, pamphlets, journals, and speeches; it gave loans to pro-Bank politicians and encouraged employers to threaten workers with losing their jobs if Jackson won. It was all for naught. The veto thrilled the voting public and drew Democrats together in resistance to the bank.

The BUS may have been popular in Pennsylvania, but so was Jackson. The rural Scots-Irish of the state gave their loyalties to one of their own blood rather than a moneyed institution. The veto message, Sen. James Webb writes in Born Fighting, “could have well emanated from a meeting of the Scottish Kirk two hundred years before.” It also cemented the loyalties of those “humble members of society—the farmers, mechanics, and laborers—who neither have the time nor the means of securing favors” to the Democratic Party for the next 175 years”...

Flash forward to 2010 elections. Once again the cries of big banks, public debt, national security, states rights, and little people against the financial elite, role of big government with banks are dominating the political landscape.

Back in the September 2009 magazine article, Scallon discusses how these issues and the actions of Andrew Jackson may allow for the formation of a modern platform to entice more conservatives and moderate Democrats into a new coalition of national, state, and regional power. If history is any guide, the lands of Kentucky will be at the center of new forces fighting to take power from the status quo. This new political power will lay claim as to who will have the right to shape and lead the state into yet another century of vast change and opportunity.

Once again, Kentucky finds itself at the edge of civilization, struggling to overcome the hardships of isolation, poverty, limited education, bank crisis and bail outs; centralization of money, and an elite ruling class removed from the day to day difficulties of living in Western or Eastern Kentucky. For Kentucky, the next 10 years will determine just how secure the state will be in facing the challenges of this new century. This is also true for the nation. History will observe that our decade of 2010 through 2020 was the defining era for which the American spirit and experiment of government was reborn and restructured.

The questions that remain to be answered:

(1) How will the concepts and principles of Andrew Jackson survive this restructuring?

(2) Will Kentucky and America be as we have known it over 200 years or

(3) Will there be a new form of government based upon corporations and expanded capitalism?

|